Students from the audiovisual school run by Development and Peace’s partner, Asociación Campesina de Antioquia (ACA), filmed this candle-lit vigil for the victims of violence that was held in Argelia, Colombia on May 4, 2021. ACA reports that although “there is so much needless violence, suffering and death,” there is also “much joy, creativity and hope in the streets.”

In 1990, the Spanish-language documentary Rodrigo D: No Futuro opened the world’s eyes to the then little-known and largely ignored reality of my homeland, Colombia. It followed the lives of a young man named Rodrigo and his friends who, born in extreme poverty and lacking the slightest possibility of improving their lot, went down paths of crime that only promised early and violent death.

That was a time of warring drug cartels in Medellín and Cali; of battles against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and other guerrillas; and of a brutal campaign of repression that became known as the “red dance,” under which government forces killed some 11,000 activists of the Patriotic Union (Unión Patriótica) party, which had emerged as a political platform for leftist rebels during a long-drawn peace process in the 1980s.

Today, more than 30 years later, it is the next generation of “Rodrigos” who are out in the streets of Colombia. Their action is becoming known as “parando para avanzar” or “stopping to advance.” They are literally risking their lives in orchestrating a stoppage, a great national strike, in the hope of moving their country forward.

A state of oppression

Since the protests began on April 28, government retaliations have left more than 800 injured and killed over 40 people. This death toll exceeds even that of the Chilean protests of 2019, which figure prominently in the regional imagination as a symbol of both public awakening and authoritarian repression.

The protestors are trying to change the Colombia that they have inherited, a country in which, like Rodrigo, they are denied lives of dignity and hope for the future. Their activism is exceptionally courageous because they grew up in an environment in which protest was stigmatized, equated to treason and criminalized. Its constitution proclaims Colombia as “a social state under the rule of law” (Article 1) that recognizes “the inalienable rights of the individual” (Article 5). In reality, however, government after government, for decades on end, has erected systemic barriers between the people and their rights.

A pattern of protests and persecution

Consider, for instance, the people’s right to education. Of the poorest fifth of Columbia’s population, only 9 per cent was enrolled in higher education, a rate that rose to 53 per cent in the wealthiest quintile1. This disparity was one of the pain points of protests that began in universities across Colombia in November 2019. Those student protestors were the protagonists of a contemporary movement whose most powerful political tool is social protest, which it has retrieved and revived from the fringes to which the state had relegated it as an obsolete, criminal and dangerous form of engagement.

Police abuse, already rampant, increased in response to the 2019 demonstrations. Media reports indicated that three people were killed, over 250 were injured and nearly 100 were arrested. The killing of a 19-year-old student, Dilan Cruz, had made international headlines at the time. It had reminded Colombians of others like 15-year-old Yuri Nicolas Neira, Jhonny Silva Aranguren, Oscar Leonardo Salas and Luis Orlando Saiz, whose killings during past demonstrations remained unpunished.

In 2020, another youth, Javier Ordóñez, was killed in the custody of the national police in Bogotá. His death sparked another huge round of protests in which, with grim predictability, nine more people were killed.

Clearly, the violent suppression that we are currently witnessing in Colombia follows a pattern. It is not new for the police to kill demonstrators. It is not new that they shoot rubber bullets at people’s eyes. It is not new for them to torture or rape detainees or to simply make them disappear.

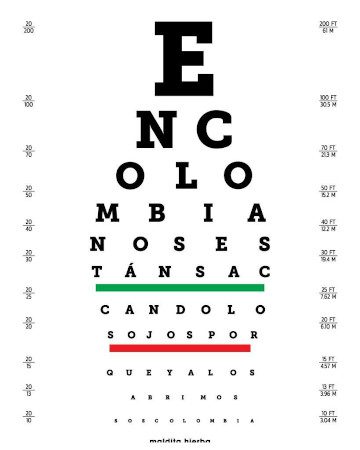

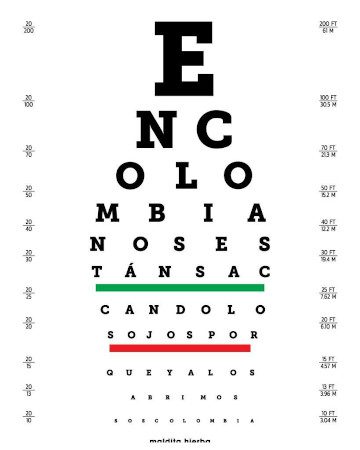

Designed as an eye chart, this protest poster reads, “In Colombia, they are gouging out our eyes because we have opened them.” It references reported instances of rubber bullets being fired at protestors’ eyes.

The roots of recent rage

Within a year of being elected in August 2018, Colombian President Iván Duque was suffering a 69 per cent disapproval rating. In November 2019, an army raid on an alleged criminal hideout in the Caquetá region left eight children dead. The revelation that the government had tried to cover up the incident cost Defence Minister Guillermo Botero his job and further damaged the president’s credibility.

Then, the pandemic arrived in 2020 and quickly worsened the widespread impoverishment and inequality. This fuelled several spontaneous protests against the Duque administration.

In April 2021, the government’s announcement of tax and healthcare “reforms” became what Monsignor Darío Monsalve, the Archbishop of Cali, called “the match that set the country on fire.” The proposed measures would widen the tax base, increase people’s tax burden, make essential products and services more expensive, and curtail access to public healthcare.

Rightly perceiving President Duque’s proposals as being totally at odds with their interests, Colombians managed to have the tax reforms struck down through nationwide strikes and protests.

An ongoing struggle

Colombians still have issues to discuss, possibly through national dialogue. Their concerns and demands include the non-privatization of pensions; the sustenance of the public health service; respect for the 2016 peace agreements with the FARC; free, universal and quality education; the right to employment; and reform of the national police, which is a paramilitary and not a civil force.

There is also widespread concern that the national elections scheduled for next year could see the rise of the ultra right. Many fear that a new government may be in the mould of President Alvaro Uribe who, during his terms from 2002 to 2010, came to be seen as fascistic, repressive and tainted by links to drug trafficking.

This is why “Rodrigo’s children” are in the streets. Their indefinite protest unites the majority—students, Indigenous people, teachers, trade unionists and artists—in an unprecedented democratic exercise. They want to stop the spiral of violence in which we Colombians have been killing each other for the last 80 years. They want a future.

Once again in my country, life is refusing to be cowed or ignored. It is dancing and singing and crying in the streets.

1) OECD (2016), “Tertiary education in Colombia”, in Education in Colombia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264250604-8-en.